|

Eric Daum was awarded a 2022 Bulfinch Award for Stewardship by the New England Chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, at the Harvard Club in Boston, on October 29th. Daum served as the inaugural President of the chapter from 2005-2009 and has sat on the board since 2005. Eric Daum's lecture on Swedish architect Martin Hedmarkfor the New England Chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art is available for viewing online.

Martin Hedmark Lecture for New England Chapter of the Institute of Classical architecture and Art11/4/2021

On Tuesday, April 20th, Eric Inman Daum will deliver his lecture on Swedish Architect Martin Hedmark. The talk was originally scheduled for Design Week Boston in conjunction with the Scandinavian Cultural Center in Newton for April 2020 but was delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The talk will be given via Zoom, and a recording of the talk will be available in the future through the ICAA. The talk is free, though registration is required. See the link below.

Martin Hedmark was a young Swedish architect who came to the United States in late 1924 to launch his career, primarily as an ecclesiastical architect for Swedish congregations and cultural institutions in America. His first commission was for Gloria Dei Lutheran Church in Providence. This unique building is an expression of two distinct early 20th Century Nordic architectural styles, the first, National Romantism was being supplanted by the second, Nordic Classicism, or Swedish Grace, around the time that Hedmark emigrated to the U.S. The lecture will explore in depth Hedmark’s designs for Gloria Dei and touch upon other projects in New York, Worcester, Philadelphia and suburban New Jersey. Eric Inman Daum served as a juror for the Palladio Awards in 2021. The Palladio Awards, held annually, recognize outstanding work in traditional design in commercial, institutional, public, and residential architecture categories. "All winners enhance the beauty and humane qualities of the built environment through creative interpretation and adaptation of design principles developed through thousands of years of architectural tradition."

The jury, including Barbara Eberlein and David Andreozzi, met virtually on March 25th to select the outstanding projects in the the many residential categories. This marked Mr. Daum's third appearence as a Palladio Awards juror, having previously served in 2015 and 2019. The upcoming news alluded to in an earlier post is that Eric Daum has joined the award-winning firm of Carpenter & MacNeille. Eric will serve in the role of Design Director of C&M's Wellesley office and is delighted to have this opportunity to join a number of old colleagues in a new venture. The Office of Eric Inman Daum Architect will continue to maintain a small presence in Andover in order to wrap up outstanding projects and continue research and writing on the career of Martin Hedmark..

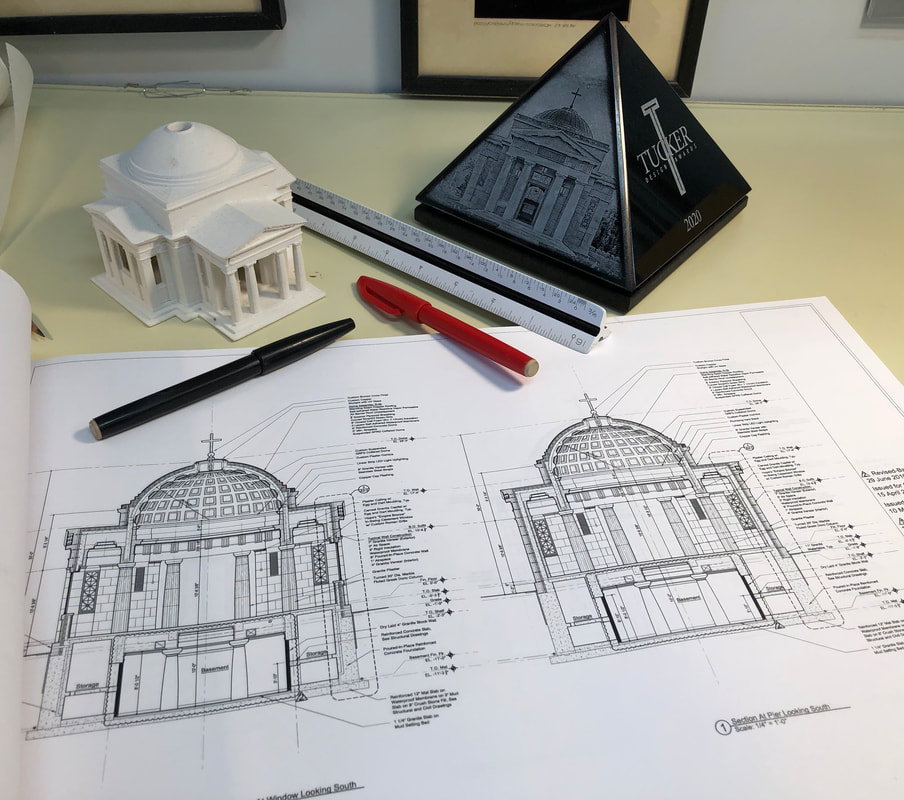

Carpenter & MacNeille Eric Inman Daum's Private Chapel received a 2020 Tucker Design Award from the Natural Stone Institute during an online ceremony on August 18, 2020. The project was nominated by NSI member Kenneth Castellucci and Associates and also recognized the the contribution of fellow NSI member Coldspring.

Tucker Design Awards Tucker Design Award Video Clip Beginning with Governor Baker's Stay at Home Order in March in reaction to the Covid-19 crisis, Eric relocated his office to his home. In the interim, the lovely Georgian Revival building in Shawsheen Village where the office has been located has been sold and will be converted into apartments. As of mid-June 2020, the office of Eric Inman Daum Architect, LLC has been moved to a new space in Downtown Andover at 11 Main Street. Begininng July 6th, there will be more news. Stay tuned...

Eric Daum was scheduled to speak at the Scandinavian Cultural Center in Newton, Massachusetts on April 2nd about the American work of Swedish Architect Martin Hedmark. Hedmark came to the United States in late 1924 and his first American project was the completion of the design for Gloria Dei Evangelical Lutheran Church in Providence, Rhode Island. This building displays many direct quotes from then contemporary National Romantic and Nordic Classical buildings in Sweden and the other Nordic nations. In late February, Eric was able to visit Hedmark's projects in New York City, Northern New Jersey, and Philadelphia. The lecture will be rescheduled for a time when it is safe to gather again. In the meantime, please be safe and isolate, and enjoy the images below. Gloria Dei Evangelical Lutheran Church, Providence, RI First Lutheran Church, Kearney, NJ Bethany Lutheran Church, Jersey City, NJ Trinity Baptist Church, New York, NY American Swedish Historical museum, Philadelphia, PA Faith Chapel, Zion Lutheran Church, Worcester, MA

My wife and I took a trip to Berlin and Vienna in November and Architectural Critic David Brussat kindly posted my thoughts about our trip on his Blog, Architecture Here and There.

Daum: Four Days in Berlin Our Private Chapel Project, completed in 2018, is featured in the December 2019 issue of Traditional Building. The article discusses in depth the historical and formal precedents that contributed to the design of this unique project.

Eric Inman Daum Architect Creates Private Mausoleum |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed